Link to paper The full paper is available here.

You can also find the paper on PapersWithCode here.

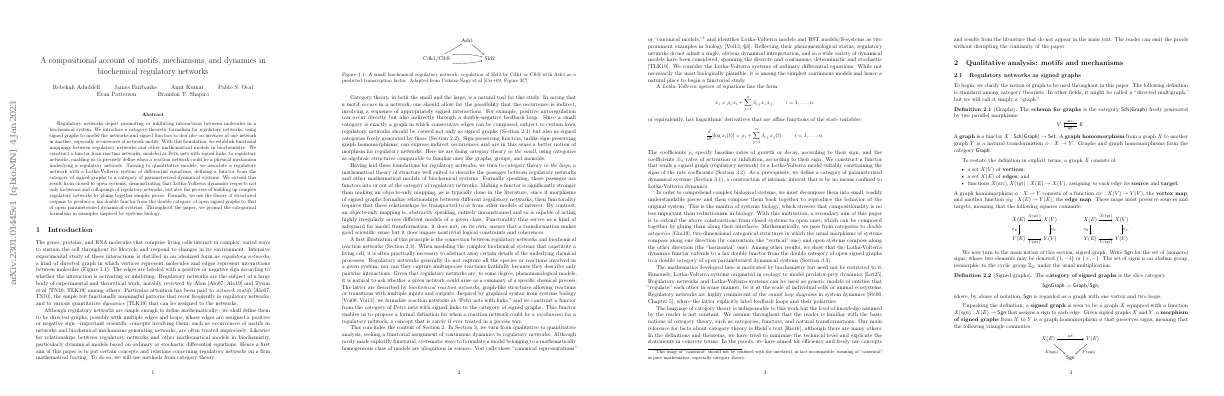

Abstract Regulatory networks depict interactions between molecules in a biochemical system Signed graphs and signed functors are used to model and describe regulatory networks Functorial mappings are established between regulatory networks and other mathematical models in biochemistry Reaction networks modeled as Petri nets with signed links can be used to define a physical mechanism underlying a regulatory network Regulatory networks can be associated with a Lotka-Volterra system of differential equations Paper Content Introduction Living cells are made up of genes, proteins, and RNA molecules These molecules interact in complex ways to sustain the cell Regulatory networks are a directed graph that represent these interactions Edges are labeled with a positive or negative sign to indicate if the interaction is activating or inhibiting Network motifs are simple patterns that recur frequently in regulatory networks Category theory is a natural tool to study regulatory networks Sign-preserving functors can express indirect occurrences Regulatory networks can be viewed as signed graphs and signed categories Functorality is a safeguard for model transformation Regulatory networks can be connected to biochemical reaction networks Functorial assignment of continuous dynamics to regulatory networks is possible Lotka-Volterra systems of equations can be used to model complex biological systems Category theory is used to extend the constructions from closed systems to open ones Double categories are used to compose open systems together Qualitative analysis: motifs and mechanisms Regulatory networks as signed graphs Definition of a graph: a functor from Sch(Graph) to Set with two parallel morphisms Graph consists of a set of vertices and edges, and functions assigning source and target to each edge Signed graph is a graph with a function assigning a sign to each edge Regulatory networks are signed graphs with vertices representing components and edges representing interactions Sign-valued matrices are a special case of signed graphs Morphisms of signed graphs can embed or collapse multiple vertices/edges Signed graphs form a well-behaved category Signed graph morphisms factor essentially uniquely as an epimorphism followed by a monomorphism Refining regulatory networks using signed categories and functors Signed morphisms do not capture the idea of refining regulatory networks Signed categories are needed to express refinement Signed categories have objects and morphisms with signs Morphisms of signed categories are called signed functors Signed functors preserve signs Signed path categories are generated by signed graphs Signed functors between signed graphs are determined by morphisms of signed graphs Positive autoregulation is an example of a network motif Instances of motifs are monic signed functors A functor maps regulatory networks to instances of motifs A commutative square of functors is used to extend the signed path category functor Mechanistic models as petri nets with links Regulatory networks summarize how components of a complex biochemical system interact Regulatory networks include only a subset of the system’s components Regulatory networks do not model individual reactions and processes, only pairwise interactions Regulatory networks are not fully mechanistic models Mechanistic models in biochemistry model individual reactions Petri nets with signed links have two types of vertices and signed edges Signed edges represent reactions with multiple inputs/outputs, consumption, and promotion/inhibition Petri nets with signed links can be approximated as signed graphs A mechanistic model for a regulatory network is a Petri net with signed links and a monic signed functor Parameterized dynamical systems Baez and Pollard extended the mass-action model of reaction networks to a functor from the category of Petri nets with rates into a category of dynamical systems Rate coefficients are often unknown and must be extracted from existing literature or estimated from experimental data The dynamics functor is nearly identical to Baez-Pollard’s The dynamics functor is the main building block in constructing a category of parameterized dynamical systems Many dynamical models depend linearly on their parameters The law of mass action and Lotka-Volterra equations are linear in the rate and affinity parameters To express important physical constraints and to define a semantics for signed graphs, the dynamical system and its parameters are restricted to be nonnegative There is a functor Dynam + : FinSet → Con that sends a finite set S to the conical space of essentially nonnegative, algebraic vector fields A conically parameterized nonnegative dynamical system consists of finite sets P and S together with a conic-linear map v : R P + → Dynam + (S) The categories of linearly and conically parameterized dynamical systems are finitely cocomplete The initial linearly parameterized dynamical system has no parameter variables, no state variables, and the unique (trivial) vector field on the zero vector space The coproduct of two linearly parameterized dynamical systems has parameter variables P 1 + P 2 , state variables S 1 + S 2 , and parameterized vector field The lotka-volterra dynamical model A Lotka-Volterra system with n species has a vector field with state vector x ∈ R n and parameters ρ ∈ R n and β ∈ R n×n The parameter ρ i sets the rate of growth or decay for species i The parameter β i,j defines a promoting or inhibiting effect of species j on species i A functor from finite graphs to linearly parameterized dynamical systems gives a semantics for unlabeled graphs A functor from finite signed graphs to conically parameterized nonnegative dynamical systems gives a semantics for regulatory networks The functor LV preserves finite colimits The morphism LV(p) sends the parameterized dynamical system with state variables {R, * } and parameters ρ, β ∈ R {R, * } + The first way sets the system’s coefficients equal to sums of the former’s coefficients The second way substitutes x * for each x i , i ∈ S, in the first system and then takes the vector field v * to be the sum of the v i ’s Composing lotka-volterra models Extending Lotka-Volterra dynamics functors between graphs and parameterized dynamical systems Vertical composition is by composition in FinSet and in Para(Dynam) Horizontal composition and monoidal products are by pushouts and coproducts in Para(Dynam) Finite sets in the feet of the cospans interpreted as linearly parameterized dynamical systems with no parameter variables and identically zero vector fields Symmetric monoidal double category Open(Para(Dynam + )) of open conically parameterized nonnegative dynamical systems Projection functor π S : Para(Dynam) → FinSet Left adjoint Z : FinSet → Para(Dynam) Symmetric monoidal double category of Z-structured cospans Double functor between open graphs and open parameterized dynamical systems Coproduct of the parameter variables for identified vertices Lax double functor LV : Open(FinGraph) → Open(Para(Dynam)) Comparison cells defined using the morphisms of linearly parameterized dynamical systems Natural transformation α S : Z(S) → LV(Disc S) Conclusion Regulatory networks are a tool to describe interactions between molecules in biochemical systems We studied regulatory networks, reaction networks, and parameterized dynamical systems We used signed graphs, Petri nets with signed links, and Lotka-Volterra dynamics We aimed to systematize the language and methods of describing, composing, and transforming scientific models We studied four different motifs in regulatory networks We discussed feedback loop analysis in system dynamics We studied open signed graphs and open parameterized dynamical systems We constructed a lax double functor between open signed graphs and open parameterized dynamical systems